Dozens of students and longtime labor activists gathered at Boston’s Democracy Brewery Nov. 23 to commemorate the 50th Anniversary of the historic Boston national “Freedom March against Racism.”

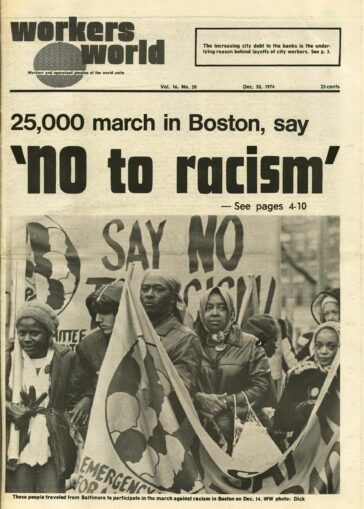

Front page Workers World, Dec. 20, 1974. (Photo: UMass Boston archives

On Dec. 14, 1974, over 25,000 demonstrators turned out — from as far away as Birmingham, Alabama, Baltimore and St. Louis — in a massive show of anti-racist solidarity with Boston’s Black community that was resisting a violent, racist mass movement in Boston hell-bent on denying equal, quality education in what was then known as the segregationist Selma, Alabama, of the North. (www.workers.org/2024/11/82098/)

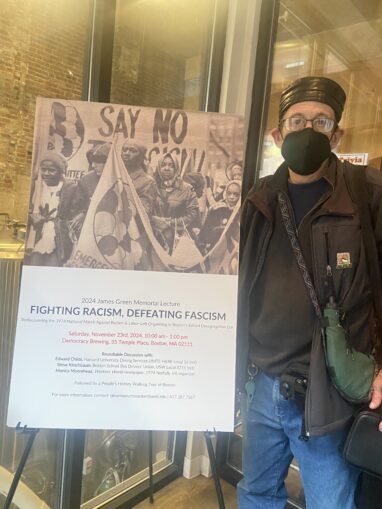

Sponsored by UMass Boston’s Labor Resource Center’s annual James Green Memorial Lecture series and chaired by UMass history professor Nick Juravich, this event opened with a slideshow compiled by Workers World organizer and former 40-year Boston school bus drivers union leader Steve Gillis that featured pictures, fliers and newspaper articles documenting the December 14 action and the united front organizing of labor and tenant unions, civil rights leaders, LGBTQIA2S+ activists, socialists and communists that made it possible.

As Gillis noted, bourgeois historians continue to ignore the rally in favor of a sanitized narrative about “forced busing.” This “tragedy”- mongering historiography — such as the 2023 PBS documentary “The Busing Battleground” which leaves the historic Dec. 14, 1974, marc h on the cutting room floor — is intended to mollify reactionaries and whitewash the roles of politicians, corporations, police forces, criminals and the Catholic church in organizing and funding the fascist movement that had roots in the widespread support in Boston of Adolph Hitler, Francisco Franco and Benito Mussolini by the Christian Front during the 1930s and 1940s. (“Nazis of Copley Square,” 2021)

Steve Gillis next to historic poster, Nov. 23, 2024. (WW photo: Mairead Skehan Gillis)

Censoring the 1974 march from mainstream history is also meant to erase the march’s lasting impact, leading to decades of victories and forward progress made possible by the successes of Boston’s Black community’s decades-long struggles for self-determination, described by historian Zebulon Vance Miletsky as Boston’s Reconstruction. (“Before Busing: A History of Boston’s Long Black Freedom Struggle,” 2022)

As the racists were unable to organize another mass mobilization after the massive and militant Dec. 14 action, the march paved the way for the future gains of the school bus drivers union and broader anti-racist and working-class struggles in Boston. Its lessons need to be known today more than ever as fascist-minded forces prepare to take the White House again.

From Reconstruction to Boston: struggle for democratic rights

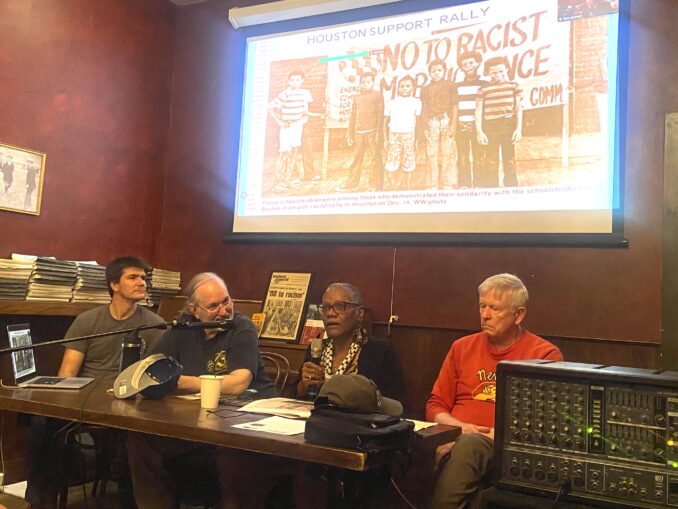

Monica Moorehead, a decades-long Workers World Party leader and a managing editor of Workers World newspaper, told of organizing two buses to the March Against Racism as a 22-year-old teacher then living in Norfolk, Virginia. She told of scenes she witnessed of racist violence and vile discrimination in Boston comparable to life in the segregated Jim Crow South of her Alabama and Texas childhood.

In her presentation, Moorehead put the 1974 march in the context of an ongoing, centuries-long struggle of Black people for self-determination, bourgeois democratic rights, reparations and liberation from the racist system of capitalist wage slavery and superexploitation. She acknowledged that the entire U.S. was land stolen from Indigenous nations.

Panelists from left to right: Nick Juravich, Stevan Kirschbaum, Monica Moorehead and Ed Childs, Boston, Nov. 23, 2024. (WW photo: Mairead Skehan Gillis)

The struggles for both desegregation and community control of public education in Boston “did not happen in a vacuum,” she explained. Rather they were a continuance of the Black resistance to the white reactionary forces like the KKK which mobilized to roll back the revolutionary gains won during the Civil War and Reconstruction. Ultimately, “these democratic rights can no longer be won under capitalism. It’s going to take a socialist revolution,” she concluded to applause.

Boston’s unfinished revolution

Ed Childs, a 50-year WWP organizer and decades-long Unite Here! Local 26 leader, described his experience infiltrating Boston’s fascist organization in 1974, ROAR (Restore Our Alienated Rights), a white supremacist terror group led by reactionary politician Louise Day Hicks, cops and other assorted bigots of the national John Birch Society, which met in city council chambers at City Hall.

ROAR’s logo was a lion smashing a school bus, and it organized weekly segregationist demonstrations of thousands in Boston’s neighborhoods during the summer and fall of 1974, as well as firebombings, snipings and daily stonings of school buses transporting Black children.

Listening in on meetings Hicks had with other ROAR ringleaders like police brass and priests, Childs gathered intelligence that allowed anti-racist organizers to outmaneuver ROAR and, ultimately, vastly outnumber their fascist cohorts on December 14 and thereafter.

Stevan Kirschbaum, an organizer with Youth Against War and Fascism (Workers World Party’s youth arm at the time) and a school bus driver from 1974 to 2024, detailed the apartheid-like regime that structured life in 1974 Boston. “If you lived in Boston, you knew this was about racism,” Kirschbaum said. “You know that what we are talking about is a struggle against racism — not about buses or federal troops or anything else.”

Kirschbaum told of first meeting Bill Owens, when Owens was in prison, through the work of WWP’s mass group the Prisoners Solidarity Committee and of Owens’ revolutionary leadership as Massachusetts’ first Black state senator in 1974. His first act was going on the offensive against the bigots as chair of the Emergency Committee for a National Mobilization Against Racism in Boston.

State Senator Bill Owens — chair of the Emergency Committee for a National Mobilization Against Racism — on top of a cop car leading marchers downtown Boston during the police attack on the march, Dec. 14, 1974. (Photo: AP)

Owens’ bold and militant leadership brought Civil Rights Movement icons like comedian Dick Gregory, Southern Christian Leadership Conference President Dr. Ralph Abernathy and Bill Lucy, a founder of the Coalition of Black Trade Unionists, to Boston on Dec. 14, fighting off a police assault and arrest of their aides during the battle on Boylston Street that day.

As Kirschbaum emphasized, it was the city’s racist police and “liberal” Brahmin class elite who enabled the racist pogroms orchestrated by ROAR. Boston segregationists may have been cosplaying as “anti-establishment” insurgents, “[getting] up in front of City Hall and the federal building,” Kirschbaum recalled, “but when you looked at the cops, they were all wearing ROAR buttons.” As Kirschbaum and other speakers stressed, the fight against the overt fascism then embodied by ROAR continues — and after Trump’s victory, has taken on new urgency.

“These MAGA forces are the ROAR of today,” Kirschbaum said. “Right now it is time to get active and organize! … We will fight and we will win. History is on our side!”

After the program, participants went on a walking tour led by UMass Boston graduate historian Maci Mark, who revisited some downtown sites of the anti-racist and labor struggles of the local teachers’ and school bus drivers’ unions, which continue to inspire today’s resistance to resurgent fascist forces.