Elon Musk has announced that he is helping to smuggle hundreds of Starlink satellite communications devices into Iran. The South African-born billionaire made the admission on December 26, replying to a tweet lauding female Iranian protesters for refusing to cover their hair. “Approaching 100 Starlinks active in Iran”, he tweeted, clearly implying a political motivation to his work.

That Musk is involved in Washington’s attempts to weaken or overthrow the administration in Tehran has been clear for some months now. In September – at the height of the demonstrations following the suspicious death of 22-year-old Iranian woman Mahsa Amini – Secretary of State Anthony Blinken announced that the U.S. was “taking action” “to advance Internet freedom and the free flow of information for the Iranian people” and “to counter the Iranian government’s censorship,” to which Musk replied, “Activating Starlink…”

While this could be understood as a positive step, unfortunately, what Washington means by internet freedom and the free flow of information (as we at MintPress News have covered before) is nothing more than the liberty of the U.S. government to flood foreign countries with relentless pro-U.S. messaging.

Starlink is an internet service allowing those with terminals to directly connect to one of over 3,000 small satellites in low Earth orbit. Many of these satellites were launched by Musk’s SpaceX technologies company. Terminals are, in effect, small, portable satellite dishes that can be used by those in the near vicinity to skirt national government restrictions on communications and get online anywhere at any time.

The process of smuggling Starlinks into Iran has been far from easy – or cheap. Each terminal has cost more than $1000 to purchase and transport, as couriers have charged high premiums on the risky cargo. Nevertheless, some sources have suggested as many as 800 have made it over the border unscathed.

Keeping Ukraine fighting

Musk’s Iran operation bears a striking resemblance to his actions earlier this year in Ukraine – another current top priority of the United States. In the aftermath of February’s Russian invasion, Musk garnered worldwide goodwill after declaring that he was “donating” thousands of Starlink terminals to Ukraine in order to keep the country online. However, these were inordinately given to the Ukrainian military and soon became the backbone of its efforts at stalling Russian advances. Ukraine’s hi-tech, Western-made weaponry relies upon online connections, the military using Starlink’s services for everything from thermal imaging, target acquisition and artillery strikes to Zoom calls.

With more than 20,000 terminals in operation, Starlink is, according to Western media, a “lifeline” and an “essential tool” without which Ukrainian resistance would have been broken. The government agrees; “SpaceX and Musk quickly react to problems and help us,” deputy prime minister Mykhailo Fedorov said recently, adding that there is “no alternative” for his forces, other than Musk’s products.

It soon transpired, however, that Musk’s donation might not have been as generous as first thought. USAID – an American government agency that has frequently functioned as a regime-change organization – had quietly paid SpaceX top dollar to send what amounted to virtually their entire inventory of Starlinks to Ukraine.

In December, Fedorov said that more than 10,000 extra terminals would shortly be heading to his country. It is not clear who will pay for these, but it is known that, two months earlier, SpaceX and the U.S. government were in negotiations about funding for additional devices to be sent to Ukraine.

Musk and the military industrial complex

While the controversial billionaire’s role in American regime change operations and proxy wars might surprise some, the reality is that, almost from the very beginning of his career, Elon Musk has enjoyed extremely close connections to the U.S. national security state.

The Central Intelligence Agency was integral to both the birth and the growth of SpaceX. Of particular importance in the company’s story is Michael Griffin, the former president and chief operating officer of the CIA’s venture capitalist wing, In-Q-Tel. In-Q-Tel was established to identify individuals and businesses that could work with or for the CIA, with the goal of maintaining the U.S. national security state’s technological edge vis-à-vis its opponents.

Griffin was an early believer in Musk, calling him a future “Henry Ford” of the rocket industry. So strong was Griffin’s desire to get the South African on board that in early 2002 (even before SpaceX had been founded) he accompanied him on a trip to Moscow in order to purchase intercontinental ballistic missiles from Russian authorities – a fact that, in today’s geopolitical reality, beggars belief.

Musk’s attempts to buy Russian rockets failed, and for many years, it appeared likely that SpaceX would be a giant flop. In 2006, the company was in difficult financial waters and was still years away from making a successful launch. But Griffin – who by this time was head of NASA – took a huge “gamble” in his own words, his organization awarding SpaceX with a $396 million contract.

Nevertheless, even this giant cash injection was not enough to stop the company hemorrhaging money. By 2008, Musk thought it likely that both SpaceX and his electric vehicle business, Tesla, would both go under. Fortunately, SpaceX was saved again by an unexpected $1.6 billion check from NASA.

Thanks to the government’s largesse, SpaceX has grown into a behemoth, employing around 11,000 people. Yet, its ties to the U.S. national security state remain as close as ever. The corporation’s primary clients are the military and other government agencies, who have paid billions of dollars to have their spy satellites and other hi-tech equipment blasted into orbit. In 2018, for example, SpaceX won a contract to deliver a $500 million Lockheed Martin GPS system into space. Although spokesmen were keen to play up the civilian benefits of the satellite, it is clear that its primary purposes were military and surveillance.

SpaceX has also won contracts with the Air Force to deliver its command satellite into orbit, with the Space Development Agency to send tracking devices into space, and with the National Reconnaissance Office to launch its spy satellites. These satellites are used by all of the “big five” surveillance agencies, including the CIA and the NSA.

This collaboration has only been growing of late. Documents obtained by The Intercept showed that the Pentagon envisages a future in which Musk’s rockets will be used to deploy a military “quick reaction force” anywhere in the world. The Department of Defense has also partnered with SpaceX in order to explore the possibility of blasting supplies into space and back to Earth, rather than flying them through the air, thereby allowing the U.S. to act faster worldwide than ever before.

And in December, SpaceX announced a new business line called Starshield, an explicitly military hardware brand that CNBC reported would be focussed on securing big money Pentagon contracts. The brand’s new motto is “supporting national security.”

Therefore, Musk and his organization can be said to be cornerstones of both the global surveillance program that individuals like Edward Snowden warned us about, and crucial to the United States’ ability to carry out endless global warfare.

Iran in the crosshairs

Ever since the revolution of 1979 that deposed the American-backed shah, Iran has been a prime target of U.S. regime change. A 2012 report from the National Endowment for Democracy explains that the U.S. is involved in a “competition” to promote color revolutions (i.e. regime change operations) in Russia, Belarus, Venezuela, Iran and other countries, while those governments seek to prevent them.

Iran has been the subject of international attention since September and the death of Mahsa Amini. Amini had been detained by Iranian authorities for not wearing a headscarf correctly. Very quickly, Western media began claiming that she had been beaten to death, an accusation that sparked nationwide protests.

Iranian authorities released footage of Amini’s collapse and medical records suggesting that she had an ongoing serious brain condition, and announced they were reviewing their policy of mandatory headcovers for women. Yet even as protests continued, they were overtaken by much more violent confrontations between authorities and Kurdish separatist movements, with Western media not caring to differentiate between them.

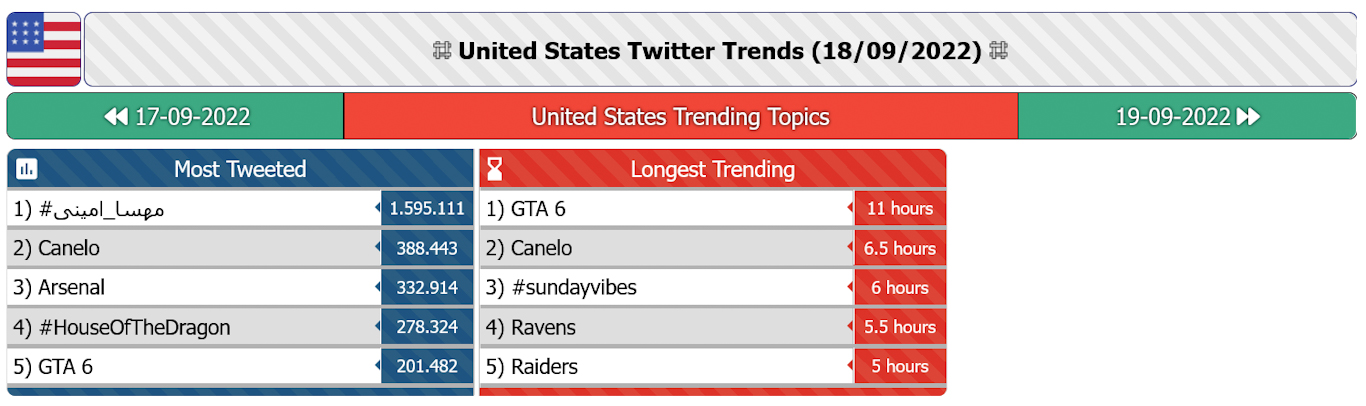

Twitter was crucial in drawing the world’s attention to Iran. The platform’s moderators put news of the protests on its “What’s Happening” sidebar, alerting users around the world to them. Pro-demonstration and anti-government hashtags were also boosted across Western countries to a remarkable degree. According to the Twitter Trending Archive, on September 18 alone, there were 1.6 million tweets from American users using the Farsi-language Amini hashtag (#مهسا_امینی). This total was beaten two days later when over 2 million tweets were sent using that hashtag, making it by far the most used in the United States that month.

In Israel, however, the astroturfing was turned up to 11. In just four days between September 21 and September 24, accounts based in Israel sent over 43 million tweets about the protests – quite an achievement, given that only around 634,000 Israelis have a Twitter account – an average of 68 tweets per account.

It is far from clear whether these huge displays of support from Western governments help or harm genuine activists in Iran. What is certain, however, is that Twitter and other big social media companies work closely with the U.S. government in order to advance attempts at regime change. Late last year, for instance, the Twitter Files revealed that the U.S. military’s Central Command (CENTCOM) had given Twitter lists of dozens of accounts it operated as part of a psychological operations program against Iran, Syria, Yemen and across the Middle East. Twitter aided them in this process, whitelisting those accounts, protecting them from scrutiny and artificially boosting their reach. Many of these accounts, The Intercept reported, accused the Iranian government of lurid crimes, including flooding Iraq with crystal meth and harvesting the organs of Afghan refugees.

This is merely the latest episode in a long history of collaboration with U.S. authorities to destabilize Iran, however. In 2009, at the behest of Washington, Twitter postponed a scheduled site maintenance which would have required taking its platform offline. It did this because the U.S.-backed leaders of a large anti-government protest were using the app to coordinate. Meanwhile, in 2020, Twitter announced that it was partnering with the FBI, and that, at the bureau’s insistence, it had removed around 130 Iranian accounts from its platform.

In addition to the cyberwar, the U.S. government is also prosecuting an economic war on the country. American sanctions have severely hurt Iran’s ability to both buy and sell goods on the open market and have harmed the value of the Iranian rial. As prices and inflation rise rapidly, ordinary people have lost their savings. Even crucial goods like medical supplies are lacking, as Washington’s maximum pressure campaign makes sure to punish businesses that trade with Iran.

Despite this, the U.S. government has been very careful to ensure that big social media companies are not affected by the sanctions and continue to operate inside Iran – a fact that suggests that Washington sees them as a crucial tool in its arsenal. Indeed, even as the State Department was announcing new rounds of sanctions, supposedly in response to Tehran’s handling of the protests, it also revealed that it was taking steps to make sure Iran was opened up as much as possible to digital communications such as WhatsApp, Facebook and Twitter.

Big tech and big government

On Iran, Silicon Valley has long collaborated with the national security state. After the Trump administration’s assassination of Iranian General Qasem Soleimani, big tech companies blocked any messages of support for the slain statesman, on the grounds that the Trump administration had declared him a terrorist. “We operate under U.S. sanctions laws, including those related to the U.S. government’s designation of the Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) and its leadership,” a Facebook spokesperson said.

This ban stood even for individuals inside Iran itself, where Soleimani was overwhelmingly popular. A University of Maryland study found that, even before he was turned into a martyr, more than 80% of the country saw Soleimani positively or very positively, making him the most admired figure in the country. This was because Soleimani and his IRGC were crucial in crushing terrorist groups like ISIS and the al-Nusra Front – a fact that Western media once frequently acknowledged. Yet Iranians were blocked from sharing majority opinions across social media and messaging apps like WhatsApp with other Iranians – even in Farsi – because of the proximity of big tech and big government.

Another indicator of how closely the national security state works with social media is the extraordinary number of former spooks and spies now work in the upper echelons of big tech corporations. Twitter itself is swarming with feds; a June MintPress study found dozens of former FBI agents working at Twitter, most of whom held influential positions in politically sensitive fields such as security, trust and safety, and content moderation. Also present at Twitter were a considerable number of ex-officials from the CIA or the Atlantic Council. Many of them directly left their jobs in government for roles at Twitter, suggesting that either the company is actively recruiting agents, or that the national security state is infiltrating social media in order to influence it.

In Part 7 of the recently-released Twitter Files, journalist Michael Shellenberger built upon this, noting that there were so many FBI agents working at Twitter that they had their own private communications channel on Slack. The former feds even created a translation cheat sheet so that agents could turn FBI jargon into its Twitter equivalent.

The FBI was instrumental in deciding what accounts to suppress and which to promote, sending the company lists of users to ban and demanding Twitter comply with its witch hunt against what it saw as an all pervasive network of Russian disinformation. When Twitter executives replied that, after investigating the FBI’s leads, they could find little to no evidence of a Russian operation of any note, the bureau became exasperated.

Thus, current FBI agents were sending information and orders to “former” feds working at Twitter in an attempt to control online speech worldwide – something that undermines the oft-quoted line that Twitter is a private company and therefore not subject to the First Amendment. It also raises profound national security questions for every other government in the world about whether they should allow a platform that is so obviously controlled by the U.S. national security state and used as a gigantic psychological operation to be available in their countries at all.

Despite this collaboration, the Twitter Files also revealed that the FBI bemoaned Twitter’s relative lack of compliance with their dictates in comparison to other big social media networks. Yet, while Musk himself has very publicly fired thousands of employees, it appears that relatively few of the spooks have been among those losing their jobs. Indeed, when asked point blankly last month “how many former FBI agents are currently employed at Twitter?” he responded with a bizarre non-answer, simply stating, “To be clear, I am generally pro-FBI, recognizing, of course, that no organization is perfect, including [the] FBI,” thereby ducking the question.

Twitter is far from alone in bringing in armies of state officials to decide what content the world sees and does not see, however. Both Facebook and Google have done the same thing, employing dozens if not hundreds of ex-CIA agents to run their internal affairs. Meanwhile, in April, a MintPress investigation uncovered what it termed a “NATO-to-TikTok pipeline”, whereby copious numbers of individuals associated with the military alliance had mysteriously changed careers to work for the video platform.

This relationship between the government and tech is far from new. In their 2013 book, “The New Digital Age,” then Google CEO Eric Schmidt and Director of Google Ideas Jared Cohen (both of whom left top national security state jobs to work for Google), wrote about how companies like theirs were fast becoming the U.S. empire’s most potent weapon in retaining Washington’s control over the modern world. As they said, “What Lockheed Martin was to the twentieth century, technology and cyber-security companies will be to the twenty-first.” Indeed, writers like Yasha Levine have argued that Silicon Valley from its very beginning was a product of the U.S. military.

While it remains to be seen what impact sending hundreds of Starlinks into Iran will have, the intention of those involved is clear. Equally plain-to-see is that big tech is not a liberatory force in modern society but is a critical weapon in the U.S.’ regime change arsenal. And while Musk continues to present himself as a renegade outsider, he has a very long history of working closely with the security state. This Iran operation is merely the latest example.

Feature photo | Illustration by MintPress News

Alan MacLeod is Senior Staff Writer for MintPress News. After completing his PhD in 2017 he published two books: Bad News From Venezuela: Twenty Years of Fake News and Misreporting and Propaganda in the Information Age: Still Manufacturing Consent, as well as a number of academic articles. He has also contributed to FAIR.org, The Guardian, Salon, The Grayzone, Jacobin Magazine, and Common Dreams.

The post How Elon Musk Is Aiding the US Empire’s Regime Change Operation in Iran appeared first on MintPress News.