When the United States decides to bring democracy to other nations, most of the world understands it as a euphemism for foreign intervention on behalf of any number of corporate and geopolitical interests. The level of involvement could range from a few USAID-linked NGOs providing ‘consultancy’ services to receptive governmental agencies all the way to remote-controlled drones and bombs dropping on innocent civilians in the name of freedom.

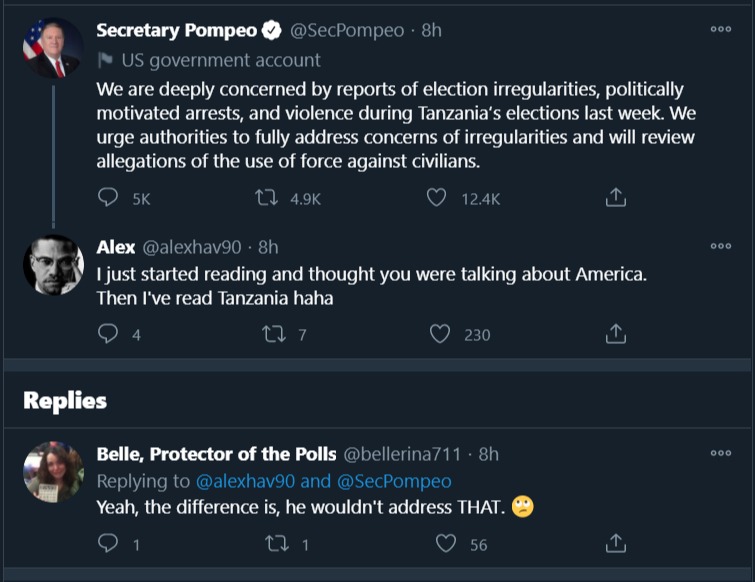

On the eve of America’s own vaunted voting ritual, incessantly propagandized as a model for countries in the Global South, it’s top diplomat is projecting the simmering electoral chaos unraveling in the United States onto other countries’ democratic processes. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo tweeted about his concerns regarding what he called the “politically motivated arrests and violence” that took place in the western African nation of Tanzania.

Given the proximity to the U.S. presidential election, Pompeo’s humble-flex diplomacy on the social media platform was misinterpreted by some as referring to America’s own “election irregularities” and “politically motivated arrests.” An understandable mistake for anyone following the U.S. election news cycle or armed with a respectable grasp of American history, for that matter.

From the mail-in ballot controversy and other voter-suppression tactics to the quintessential political imprisonments of Julian Assange and the all-but-forgotten Native American civil rights activist, Leonard Peltier, – who has been languishing in federal prison for decades – the contours of the 2020 U.S. election are bleeding into elections across the world.

Tanzania, the country Pompeo was actually chastising in his tweet, has ties to the U.S. establishment that date back to the 1960s, before it even existed, as such. As the Cold War peaked, Frank Carlucci – Reagan’s future national security adviser and defense secretary – was the U.S. consul in Zanzibar, which was considered a communist hot spot after the revolution toppled the Sultanate in 1964.

The ploy to undermine the independent government of Zanzibar entailed making it part of a new country called Tanzania by exploiting Pan-African sensibilities, which were strong at the time, to convince the neighboring Republic of Tanganyika to join forces. All the while, spooks like Carlucci were whispering in the ear of the leadership in both countries on behalf of the U.S./UK axis, which wanted Zanzibar’s capacity for self-determination thwarted.

Perhaps coincidentally, the current U.S. Ambassador to Tanzania, was also in Zanzibar just after the new country was formed as a volunteer physician at a public hospital. Dr. Donald J. Wright was nominated by President Trump in September of 2019 and was sworn in as the sixteenth United States Ambassador to the United Republic of Tanzania on April 2, 2020.

Blogging diplomacy

Wright, a physician who began his civil service career at the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), was tapped by the Trump administration while serving as the Deputy Assistant Secretary for Health at the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS). In his statement to the Senate Foreign Relations Committee at his confirmation hearing, he specifically mentions the 2020 elections in Tanzania, promising to continue “the work of our embassy to encourage a fair, free, transparent and inclusive election.”

Settled in his new post by the time the election rolled around, ambassador Wright got the ball rolling a week before the vote on October 28th by questioning the African nation’s democracy, asserting in an op-ed published on the embassy’s website that it risked losing “credibility in the eyes of the international community” over reports of government interference and political violence.

Communiques from the U.S. Embassy after the election claimed that “significant election-related fraud and intimidation” had occurred during Wednesday’s presidential election, which resulted in the re-election of President John Pombe Magufuli, who is a member of the ruling party. Tanzanian opposition leaders were reportedly arrested and detained after calling for an election re-do and planning widespread protests over the contested vote.

A problematic statesman

The focus of Pompeo’s departmental subordinate on the integrity of the Tanzanian election was expressed in early October, as well, when he actually threatened consequences “for those found responsible for violence or frustrating the democratic process,” according to Tanzanian daily The Citizen. In a statement issued by the American diplomatic outpost on October 1, the U.S. warned that Tanzania’s elections had implications for the entire East African region.

This narrative, always couched with the usual disclaimers of impartiality in keeping with the pretense of democratic values, has been fostered for months via powerful international policy channels like the Council on Foreign Relations. In August, the powerful D.C. think tank published a screed noting that president Magufuli was becoming “increasingly problematic” in the eyes of John Campbell, Senior Fellow for Africa Policy Studies and the blog post’s author.

Campell rebuked Magufuli’s reticence to “share” information with international health agencies regarding COVID-19 and branded him an authoritarian for rejecting the “usual protocols” deemed necessary for containing the disease.

It is clear that Magufuli’s perceived sins are impinging on certain, long-standing relationships between the U.S. and Tanzanian healthcare organizations. As the “leading donor” for “the development of health services” in the African country, Pompeo’s social media calls to “fully address concerns of irregularities” is boilerplate code to provide cover for other, less transparent motives.

Every trick in the book

In May, the official Twitter account of the U.S. Embassy in Tanzania claimed that COVID-19 cases in its largest city, Dar es Salaam, were “extremely high” despite offering no evidence. A CNN article repeats many of the same tropes ascribed to Magufuli as a result of his refusal to lockdown his country, such as claims that he suggested people “pray the virus away,” which was also brought up by Campbell in his CFR piece months later.

The sudden uptick in pressure from the U.S. State Department over the Tanzanian election results is a clear indication that Washington did not achieve its desired outcome. Beyond the personal beliefs Magufuli may or may not have about how to best combat the pandemic crisis, Wednesday’s triumph was also accompanied by a landslide victory by his party, which picked up 97% of seats in parliament. That number is more than enough to change the nation’s constitution, which was created in 1977 after the creation of modern-day Tanzania through the merger of the People’s Republic of Zanzibar and the Republic of Tanganyika in the mid-sixties.

This largely unexpected union in a heavily conflicted region of Africa at the height of the Cold War was fostered by the U.S., Britain, and West Germany, who were trying to proscribe any influence Zanzibar, which had successfully overthrown the Sultan of Zanzibar in the 1964 revolution and considered to be a “surrogate” of Soviet Russia and other communist powers, by subsuming the newly independent country under a joint government with the more malleable Prime Minister of Tanganyika, Julius Nyerere, at its head.

The CIA and the U.S. State Department via Dean Rusk placed enormous pressure on Nyerere to bring the leaders of the Zanzibar revolution under control once the union was executed. Nyereye proved up to the task, jailing one of the revolution’s most prominent figures in 1972 – Abdulrahman Mohamed Babu, who was serving as one of Nyerere’s ministers under the new U.S.-sanctioned regime.

Nearly fifty years later, American interests in the region remain strong and with the revival of McCarthyist rhetoric emanating from Washington, it looks as though the artificially imposed arrangements by Atlanticist powers on the people of Tanzania has begun to fray at the seams.

Unlike his predecessors, Pompeo can project his policy directives through character-limited posts on social media platforms which have long been outed as tools of U.S. foreign policy. It is unclear, however, if this kind of instant-mix, digital diplomacy can avoid the inevitable collapse of a system created to serve the interests of foreign powers or stem the rise of a true pan-African nationalism as envisioned by Babu, Fanon, and other enemies of the colonial juggernaut who, since the days of Cecil Rhodes, have pulled every trick in the book to keep the entire continent under its hypnotic sway.

Feature photo | U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo walks to board an aircraft to leave for Maldives, in Colombo, Sri Lanka, Oct. 28, 2020. Eranga Jayawardena | AP

Raul Diego is a MintPress News Staff Writer, independent photojournalist, researcher, writer and documentary filmmaker.

The post Pompeo’s Tweet About Tanzania Election Irregularities Could Have Easily Been About the US appeared first on MintPress News.