AD-DUMAYR, SYRIA — A little over a year ago — just after the Syrian army and its allies liberated the towns and villages around eastern Ghouta from the myriad armed jihadist groups that had waged a brutal campaign of torture and executions in the area — I interviewed a number of the civilians that had endured life under jihadist rule in Douma, Kafr Batna and the Horjilleh Center for Displaced People just south of Damascus.

A common theme emerged from the testimonies of those civilians: starvation as a result of jihadist control over aid and food supplies, and the public execution of civilians.

Their testimonies echoed those of civilians in other areas of Syria formerly occupied by armed anti-government groups, from Madaya and al-Waer to eastern Aleppo and elsewhere.

Despite those testimonies and the reality on the ground, Western politicians and media alike have placed the blame for the starvation and suffering of Syrian civilians squarely on the shoulders of Russia and Syria, ignoring the culpability of terrorist groups.

In reality, terrorist groups operating within areas of Syria that they occupy have had full control over food and aid, and ample documentation shows that they have hoarded food and medicines for themselves. Even under better circumstances, terrorist groups charged hungry civilians grotesquely inflated prices for basic foods, sometimes demanding up to 8,000 Syrian pounds (US $16) for a kilogram of salt, and 3,000 pounds (US $6) for a bag of bread.

Given the Western press’ obsessive coverage of the starvation and lack of medical care endured by Syrian civilians, its silence has been deafening in the case of Rukban — a desolate refugee camp in Syria’s southeast where conditions are appalling to such an extent that civilians have been dying as a result. Coverage has been scant of the successful evacuations of nearly 15,000 of the 40,000 to 60,000 now-former residents of Rukban (numbers vary according to source) to safe havens where they are provided food, shelter and medical care.

Silence about the civilian evacuations from Rukban is likely a result of the fact that those doing the rescuing are the governments of Syria and Russia — and the fact that they have been doing so in the face of increasing levels of opposition from the U.S. government.

A harsh, abusive environment

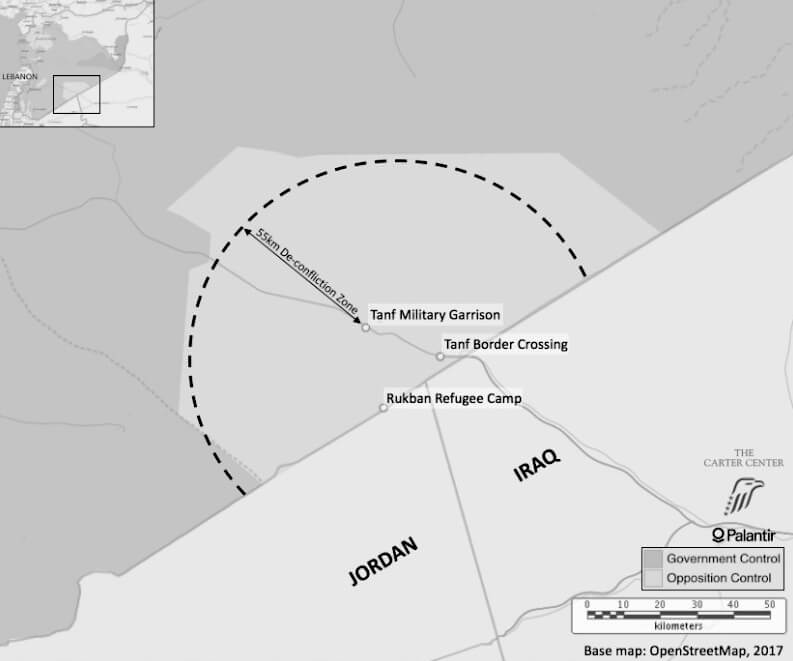

Rukban lies on Syria’s desolate desert border with Jordan, surrounded by a 55-km deconfliction zone, unilaterally established and enforced by the United States, and little else aside from the American base at al-Tanf, only 25 km away — a base whose presence is illegal under international law.

It is, by all reports, an unbearably harsh environment year-round and residents of the camp have endured abuse by terrorist groups and merchants within the camp, deprived of the very basics of life for many years now.

In February, the UNHCR reported that young girls and women in Rukban have been forced into marriage, some more than once. Their briefing noted:

Many women are terrified to leave their mud homes or tents and to be outside, as there are serious risks of sexual abuse and harassment. Our staff met mothers who keep their daughters indoors, as they are too afraid to let them go to improvised schools.”

The Jordanian government, home to 664,330 registered Syrian refugees, has adamantly refused any responsibility in providing humanitarian assistance to Rukban, arguing that it is a Syrian issue and that keeping its border with Syria closed is a matter of Jordan’s security — this after a number of terrorist attacks on the border near Rukban, some of which were attributed to ISIS and one that killed six Jordanian soldiers.

According to U.S. think-tank The Century Foundation, armed groups in Rukban have up to 4,000 men in their ranks and include:

Maghawir al-Thawra, the Free Tribes Army, the remnants of a formerly Pentagon-backed group called the Qaryatein Martyr Battalions and three factions formerly linked to the CIA’s covert war in Syria: the Army of the Eastern Lions, the Martyr Ahmed al-Abdo Forces, and the Shaam Liberation Army.”

Those armed groups, according to Russia, include several hundred ISIS and al-Qaeda recruits. Even the Atlantic Council — a NATO- and U.S. State Department-funded think-tank consistent in its anti-Syrian government stance — reported in November 2017 that the Jordanian government acknowledged an ISIS presence in Rukban.

The Century Foundation also notes the presence of ISIS in Rukban and concedes that the U.S. military “controls the area but won’t guarantee the safety of aid workers seeking access to the camp.”

The Rukban camp, sandwiched between Jordan, Syria borders and Iraq, Feb. 14, 2017. Raad Adayleh | AP

Syria and Russia have sought out diplomatic means to resolve the issue of Rukban, arguing repeatedly at the United Nations Security Council for the need to dismantle the camp and return refugees to areas once plagued by terrorism but that have now been secured.

As I wrote recently:

The U.S. stymied aid to Rukban, and was then only willing to provide security for aid convoys to a point 10 kilometres (6.2 miles) away from the camp, according to the UN’s own Emergency Relief Coordinator, Mark Lowcock. So, by U.S. administration logic, convoys should have dropped their Rukban-specific aid in areas controlled by terrorist groups and just hoped for the best.”

The U.S., for its part, has both refused the evacuation of refugees from the camp and obstructed aid deliveries on at least two occasions. In February, Russia and Syria opened two humanitarian corridors to Rukban and began delivering much-needed aid to its residents.

Syria’s Permanent Representative to the United Nations, Ambassador Bashar al-Ja’afari, noted in May 2019 that Syria agreed to facilitate the first aid convoy to Rukban earlier this year, but the convoy was ultimately delayed by the United States for 40 days. A second convoy was then delayed for four months. Al-Ja’afari also noted that the U.S., as an occupying power in Syria, is obliged under the Geneva Conventions to provide food, medicine and humanitarian assistance to those under its occupation.

Then, in early March, the Russian Center for Reconciliation reported that U.S. authorities had refused entry to a convoy of buses intending to enter the deconfliction zone to evacuate refugees from Rukban.

According to a March 2019 article from Public Radio International:

[W]hen Syrian and Iranian forces have entered the 34-mile perimeter around the base, American warplanes have responded with strikes — effectively putting Rukban and its residents under American protection from Assad’s forces.”

Despite the abundance of obstacles they faced, Syria and Russia were ultimately able to evacuate over 14,000 of the camp’s residents to safety. In a joint statement on June 19, representatives of the two countries noted that some of the camp’s residents were forced to pay “militants” between $400 to $1000 in order to leave Rukban.

Media reports on Rukban … from abroad

While Rukban — unlike Madaya or Aleppo in 2016 — generally isn’t making headlines, there are some pro-regime-change media reporting on it, although even those reports tend to omit the fact that civilians have been evacuated to safety and provided with food and medical care.

Instead, articles relieve America and armed Jihadist groups of their role in the suffering of displaced Syrians in Rukban, reserving blame for Syria and Russia and claiming internal refugees are being forced to leave against their will only to be imprisoned by the Syrian government.

Emad Ghali, a “media activist,” has been at the center of many of these claims. Ghali has been cited as a credible source in most of the mainstream Western press’ reporting on Rukban, from the New York Times, to Al Jazeera, to the Middle East Eye. Cited since at least 2018 in media reporting on Rukban, Ghali has an allegiance to the Free Syrian Army, a fact easily gleaned by simply browsing his Facebook profile. He recently posted multiple times on Facebook mourning the passing of jihadist commander and footballer Abdul Baset al-Sarout. As it turns out, Sarout not only held extremist and sectarian views, but pledged allegiance to ISIS, among other less-than-noble acts ignored by most media reports that cite him.

Ghali paid homage to ISIS commander Abdul Baset al-Sarout on his Facebook page

Citing Ghali as merely a “media activist” is not an unusual practice for many covering the Syrian conflict. In fact, Ghali holds the same level of extremist-minded views as the “sources” cited by the New York Times in articles that I reported on around the time Ghouta was being liberated from jihadist groups in 2018.

Four sources used in those articles had affiliations to, and/or reverence for the al-Qaeda-linked Jaysh al-Islam — including the former leader Zahran Alloush who has been known to confine civilians in cages, including women and children, for use as human shields in Ghouta — Faylaq al-Rahman, and even to al-Qaeda, not to mention the so-called Emir of al-Qaeda in Syria, the applauded Abu Muhammad Al-Julani.

Claims in a Reuters article of forced internment, being held at gunpoint in refugee centers, come from sources not named in Rukban — instead generically referred to as “residents of Rukban say”…

An article in the UAE-based The National also pushed fear-mongering over the “fate that awaits” evacuees, saying:

[T]here is talk of Syrian government guards separating women and children from men in holding centres in Homs city.There are also accusations of a shooting last month, with two men who had attempted an escape from one of the holding centres allegedly killed. The stories are unconfirmed, but they are enough to make Rukban’s men wary of taking the government’s route out.”

Yet reports from those who have actually visited the centers paint a different picture.

An April 2019 report by Russia-based Vesti News shows calm scenes of Rukban evacuees receiving medical exams by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent, who according to Vesti, have doctors there every day; and of food and clean, if not simple, rooms in a former school housing displaced refugees from Rukban. Notably, the Vesti journalist states: “There aren’t any checkpoints or barriers at the centre. The entrance and exit are free.”

The Russian Reconciliation Center reported on May 23 of the refugee centers:

In early May, these shelters were visited by officials from the respective UN agencies, in particular, the UNHCR, who could personally see that the Syrian government provided the required level of accommodation for the refugees in Homs. It is remarkable that most of the former Rukban residents have already relocated from temporary shelters in Homs to permanent residencies in government-controlled areas.”

Likewise, in the Horjilleh Center which I visited in 2018 families were living in modest but sanitary shelters, cooked food was provided, a school was running, and authorities were working to replace identity papers lost during the years under the rule of jihadist groups.

Calling on the U.S. to close the camp

David Swanson, Public Information Officer Regional Office for the Syria Crisis UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs based in Amman, Jordan, told me regarding claims of substandard conditions and of Syrians being forcefully held or mistreated in the centers that,

People leaving Rukban are taken to temporary collective shelters in Homs for a 24-hour stay. While there, the receive basic assistance, including shelter, blankets, mattresses, solar lamps, sleeping mats, plastic sheets, food parcels and nutrition supplies before proceeding to their areas of choice, mostly towards southern and eastern Homs, with smaller small numbers going to rural Damascus or Deir-ez-Zor.

The United Nations has been granted access to the shelters on three occasions and has found the situation there adequate. The United Nations continues to advocate and call for safe, sustained and unimpeded humanitarian assistance and access to Rukban as well as to all those in need throughout Syria. The United Nations also seeks the support of all concerned parties in ensuring the humanitarian and voluntary character of departures from Rukban.”

Hedinn Halldorsson, the Spokesperson and Public Information Officer for the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) based in Damascus, told me:

We looked into this when the rumours started, end of April, and concluded they were unfounded – and communicated that externally via press briefings in both Geneva and NY. The conditions in the shelters in Homs are also adequate and in compliance with standards; the UN has access and has done three monitoring visits so far.”

Syrian Arab Red Crescent members unload food and water for Rukban’s evacuees. Photo | Eva Bartlett

Halldorsson noted official UN statements, including:

“Alleged mistreatment of Rukban returnees

- The United Nations is aware of media reports about people leaving Rukban having been killed or subject to mistreatment upon arrival in shelters in Homs.

- The United Nations has not been able to confirm any of the allegations.

Regarding the issue of shelters, Halldorsson noted that as of July 1st:

- Nearly 15,600 people have left Rukban since March – or nearly 40 per cent of the estimated total population of 41,700.

- The United Nations has been granted access to the shelters in Homs on three occasions and found conditions in these shelters to be adequate.”

Confirming both UN officials’ statements about the Syrian government’s role in Rukban, the Syrian Mission to the United Nations in New York City told me:

The Syrian Government has spared no effort in recent years to provide every form of humanitarian assistance and support to all Syrians affected by the crisis, regardless of their locations throughout Syria. The Syrian Government has therefore collaborated and cooperated with the United Nations and other international organizations working in Syria to that end, in accordance with General Assembly resolution 46/182.

There must be an end to the suffering of tens of thousands of civilians who live in Al-Rukban, an area which is controlled by illegitimate foreign forces and armed terrorist groups affiliated with them. The continued suffering of those Syrian civilians demonstrates the indifference of the United States Administration to their suffering and disastrous situation.

We stress once again that there is a need to put an end to the suffering of these civilians and to close this camp definitively. The detained people in the camp must be allowed to leave it and return to their homes, which have been liberated by the Syrian Arab Army from terrorism. We note that the Syrian Government has taken all necessary measures to evacuate the detainees from the Rukban camp and end their suffering. What is needed today is for the American occupation forces to allow the camp to be dismantled and to ensure safe transportation in the occupied Al-Tanf area.”

Given that the United States has clearly demonstrated not only a lack of will to aid and or resettle Rukban’s residents but a callousness that flies in the face of their purported concern for Syrians in Rukban, the words of Syrian and Russian authorities on how to solve the crisis in Rukban could not ring truer.

Very little actual coverage

The sparse coverage Rukban has received has mostly revolved around accusations that the camp’s civilians fear returning to government-secured areas of Syria for fear of being imprisoned or tortured. This, in spite of the fact that areas brought back under government control over the years have seen hundreds of thousands of Syrian civilians return to live in peace and of a confirmation by the United Nations that they had “positively assessed the conditions created by the Syrian authorities for returning refugees.”

The accusations also come in spite of the fact that, for years now, millions of internally displaced Syrians have taken shelter in government areas, often housed and given medical care by Syrian authorities.

Over the years I’ve found myself waiting for well over a month for my journalist visa at the Syrian embassy in Beirut to clear. During these times I traveled around Lebanon where I’ve encountered Syrians who left their country either for work, the main reason, or because their neighborhoods were occupied by terrorist groups. All expressed a longing for Syria and a desire to return home.

In March, journalist Sharmine Narwani tweeted in part that, “the head of UNDP in Lebanon told me during an interview: ‘I have not met a single Syrian refugee who does not want to go home.’”

Of the authors who penned articles claiming that Syrians in Rukban are afraid to return to government-secured areas of Syria, few that I’m aware of actually traveled to Syria to speak with evacuees, instead reporting from Istanbul or even further abroad.

On June 12, I did just that, hiring a taxi to take me to a dusty stretch of road roughly 60 km east of ad-Dumayr, Syria, where I was able to intercept a convoy of buses ferrying exhausted refugees out of Rukban.

Merchants, armed groups and Americans

Five hundred meters from a fork in the highway connecting a road heading northeast to Tadmur (Palmyra) to another heading southeast towards Iraq — I waited at a nondescript stopping point called al-Waha, where buses stopped for water and food to be distributed to starving refugees. In Arabic, al-Waha means the oasis and, although only a makeshift Red Crescent distribution center, and compared to Rukban it might as well have been an oasis.

A convoy of 18 buses carrying nearly 900 tormented Syrians followed by a line of trucks carrying their belongings were transferred to refugee reception centers in Homs. Members of the Syrian Arab Red Crescent distributed boxes containing beans, chickpeas and canned meat — the latter a scarcity among the displaced.

Buses transported nearly 900 refugees from Rukban Camp to temporary shelters in Homs on June 12. Photo | Eva Bartlett

As food and water were handed out, I moved from bus to bus speaking with people who endured years-long shortages of food, medicine, clean water, work and education … the basic essentials of life. Most people I spoke to said they were starving because they couldn’t afford the hefty prices of food in the camp, which they blamed on Rukban’s merchants. Some blamed the terrorist groups operating in the camp and still others blamed the Americans. A few women I spoke to blamed the Syrian government, saying no aid had entered Rukban at all, a claim that would later be refuted by reports from both the UN and Red Crescent.

An old woman slumped on the floor of one bus recounted:

We were dying of hunger, life was hell there. Traders [merchants] sold everything at high prices, very expensive; we couldn’t afford to buy things. We tried to leave before today but we didn’t have money to pay for a car out. There were no doctors; it was horrible there.”

An elderly woman recounted enduring hunger in Rukban. Photo | Eva Bartlett

Aboard another bus, an older woman sat on the floor, two young women and several babies around her. She had spent four years in the camp: “Everything was expensive, we were hungry all the time. We ate bread, za’atar, yogurt… We didn’t know meat, fruit…”

Merchants charged 1,000 Syrian pounds (US $2) for five potatoes, she said, exemplifying the absurdly high prices.

I asked whether she’d been prevented from leaving before. “Yes,” she responded.

She didn’t get a chance to elaborate as a younger woman further back on the bus shouted at her that no one had been preventing anyone from leaving. When I asked the younger woman how the armed groups had treated her, she replied, “All respect to them.”

But others that I spoke to were explicit in their blame for both the terrorist groups operating in the camp and the U.S. occupation forces in al-Tanf.

An older man from Palmyra who spent four years in the camp spoke of “armed gangs” paid in U.S. dollars being the only ones able to eat properly:

The armed gangs were living while the rest of the people were dead. No one here had fruit for several years. Those who wanted fruit have to pay in U.S. dollars. The armed groups were the only ones who could do so. They were spreading propaganda: ‘don’t go, the aid is coming.’ We do not want aid. We want to go back to our towns.”

Mahmoud Saleh, a young man from Homs, told me he’d fled home five years ago. According to Saleh, the Americans were in control of Rukban. He also put blame on the armed groups operating in the camp, especially for controlling who was permitted to leave. He said, “There are two other convoys trying to leave but the armed groups are preventing them.”

Mahmoud Saleh from Homs said the Americans control Rukban and blamed armed groups in the camp for controlling who could leave. Photo | Eva Bartlett

A shepherd who had spent three years in Rukban blamed “terrorists” for not being able to leave. He also blamed the United States: “Those controlling Tanf wouldn’t let us leave, the Americans wouldn’t let us leave.”

Many others I spoke to said they had wanted to leave before but were fear-mongered by terrorists into staying, told they would be “slaughtered by the regime,” a claim parroted by many in the Western press when Aleppo and other areas of Syria were being liberated from armed groups.

The testimonies I heard when speaking to Rukban evacuees radically differed from the claims made in most of the Western press’ reporting about Syria’s treatment of refugees. These testimonies are not only corroborated by Syrian and Russian authorities, but also by the United Nations itself.

Feature photo | An elderly women evacuated from Rukban complained of hunger due to extremely high food prices. Photo | Eva Bartlett

Eva Bartlett is a Canadian independent journalist and activist. She has spent years on the ground covering conflict zones in the Middle East, especially in Syria and occupied Palestine, where she lived for nearly four years. She is a recipient of the 2017 International Journalism Award for International Reporting, granted by the Mexican Journalists’ Press Club (founded in 1951), was the first recipient of the Serena Shim Award for Uncompromised Integrity in Journalism, and was short-listed in 2017 for the Martha Gellhorn Prize for Journalism. See her extended bio on her blog In Gaza. She tweets at @EvaKBartlett

The post Voices from Syria’s Rukban Refugee Camp Belie Corporate Media Reporting appeared first on MintPress News.