CHICAGO — “Shorty!”

Ricky Maclin bellowed at the secretary in a stairwell at Republic Windows and Doors, trying to get her attention. She was one of the few black temps in the secretarial pool; he was vice-president of the union local, the lone black on its executive board. The two of them got along like the proverbial house afire, and on more than one occasion Shorty had even shared with Ricky the contents of a memo that she’d come across, or a conversation she’d overheard, when the plant’s management was dragging its feet or flat-out lying to the union about some issue or another.

But on this late November morning in 2008, as the pair walked past each other on the stairs, Ricky’s greeting went unacknowledged; the diminutive secretary clearly had things on her mind.

Ricky blurted out: “You didn’t get the ax, did you?”

“No,” she answered:

But Ricky, I don’t know if I’m going to make it through the day. When we got into work this morning, everything was gone: our desks, our computers, the file cabinets. We didn’t have chairs to sit on. We had to go to the cafeteria, grab some folding chairs and carry them upstairs just so we’d have a place to sit.”

Equipment had begun vanishing from Republic Windows and Doors on Chicago’s North Side just days before Halloween: first a punch press, then the big industrial saws that cut through fiberglass, the machines that spat out plastic moldings for the windows, and another that wrapped them for shipping. That same month, the company let go 30 workers, followed by another 15 in early November. After some detective work, the union suspected that management was moving operations to another factory in Red Oaks, Iowa, that made replacement windows for industrial buildings. All 102 employees were non-union.

Ricky asked the temp if the secretarial pool had complained to management, and she responded with a grimace as if to signal the question was silly. “Hell no, we didn’t say nothing Ricky. We don’t have a union like y’all do.

Could Alito ruling wind up democratizing unions?

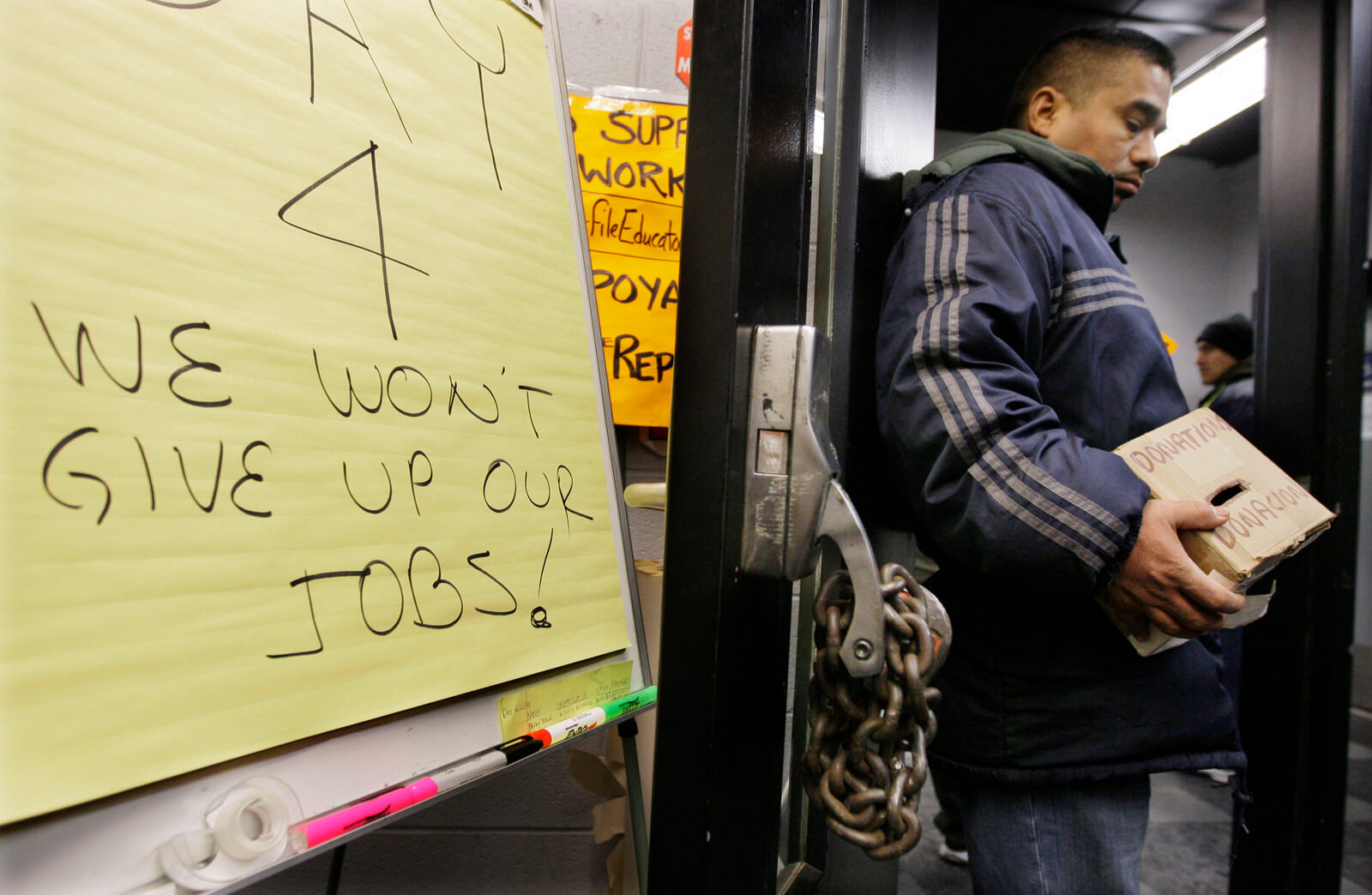

Fielipe Dillado, a ten year employee, holds a donation box on the fourth day of a sit-in at the Republic Windows and Doors factory, Dec. 8, 2008 in Chicago. M. Spencer Green | AP

A six-day occupation of Republic Windows and Doors by 240 cashiered workers in the final days of 2008 shocked the nation. Not only did the mostly-Latino and African American workforce win a severance package, back pay and other benefits owed them after the factory closed, but they also won broad public support — including from the president-elect, Barack Obama — went on to form a worker-owned cooperative, and shined a light on the potential of organized labor in the 21st century.

The conventional wisdom is that the U.S. Supreme Court dealt an ultimately fatal blow to organized labor when it ruled that non-members cannot be forced to pay fees to unions representing public-sector employees, cutting off a financial spigot for the labor unions. But the decision could actually prove to be a good thing in the long-run by democratizing labor unions and revitalizing a moribund movement that was the engine of America’s postwar prosperity.

In 2004, Maclin and Republic’s mostly black and brown workers had ousted as their representative a corrupt, mobbed-up Teamsters union that was still led by white ethnics who wore pinkie rings, slicked back their hair, never seemed interested in coaxing the company to increase its contribution to the employees’ health insurance plan, and always seemed to have their hand in the workers’ pension fund. So chummy was the union leadership with management that it once joined the company in exhorting striking workers to return to their jobs. And it was the company’s owner who led the campaign — complete with picnics, ice-cream socials and remodeled cafeteria — against the workers’ ultimately successful bid to decertify the union and replace it with the progressive United Electrical Radio and Machine Workers of America, better known as UE.

Workers have for decades complained that dues check-offs — the company’s automatic deductions from employees’ paychecks and transfer to the union leadership — are a part of an unwritten pact between mostly white union leaders and mostly white corporate executives to control a workforce that is increasingly darker-skinned and more radical.

Rich Gibson, a labor organizer and emeritus professor of history and education at San Diego State University wrote in a 2013 essay:

The Union tops sell a pacified or disciplined workforce for money from employers. That is the nucleus of “collective bargaining.

Employers collect dues (check-off) on behalf of the union, send it to the union heads, while the labor tops promise labor peace for the duration of the contract. That is precisely the traditional exchange. Labor heads use violence to ‘protect the contract,’ because employers can sue them if the rank and file (goes on a) wildcat (strike). . . Unions become the bosses enforcers.”

When his executives explained the dues check-off arrangement to Henry Ford, the notoriously anti-union automaker is reported to have said:

You mean I’m the union’s banker? Sign me on!”

Automatic dues check-off was a principal target of the Dodge Revolutionary Union Movement, or DRUM, an organization of radical, black auto workers frustrated by racism they faced both from their boss and from their representatives within the United Auto Workers. The employers’ automatic deduction from workers’ paychecks meant that rank-and-file workers could not hold their union accountable; it was, in effect, anti-democratic.

In July of 1968, 3,000 black workers went on a two-day wildcat strike of a Chrysler plant in Detroit. In her book Guerillas in the Industrial Jungle: Radicalism’s Primitive and Industrial Rhetoric, author Ursula Taggart wrote:

Both Chrysler and UAW Local 3, DRUM argued, were responsible for the plight of black workers and the organization demanded concessions from each. From the corporation, it demanded an exhaustive list of black foremen, managers and executives in addition to equal wages for whites and blacks and amnesty for fired workers. From the union it requested more blacks on staff, especially at the executive levels, a revision of the grievance procedure, better safety protections, guards against speed-ups, recognition of DRUM as the official voice of black workers, a decrease in union dues, UAW investment but not interference in the black community, an end to the check-off system of union dues, and a general strike against the Vietnam War.

Making union leaders sing for their supper

Brian Parker, strategic action coordinator for the Transport Workers Union, addresses a crowd before a protest march at Dallas/Fort Worth International Airport in Grapevine, Texas, July 26, 2017. LM Otero | AP

The 5 – 4 Supreme Court ruling Wednesday in Janus v. AFSCME overturned a 1977 court decision to permit so-called “agency fees,” which have been collected from millions of workers who choose not to join unions but are still protected by collective bargaining agreements.

Forcing non-members to pay these fees to unions whose views they may oppose violates their rights to free speech and free association under the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, the Court said in the ruling authored by Justice Samuel Alito.

Labor leaders say that while the ruling only applies to a narrow slice of public sector workers, it will almost certainly bleed into the private sector in short order. In a dissent, Justice Elena Kagan accused the court’s conservatives of “weaponizing the First Amendment” to intervene in economic and regulatory policy.

But black and brown workers say that anything that helps restore democracy and accountability in organized labor is a positive step forward. By making labor leaders in effect, sing for their supper, it can weaken collaboration between white union bosses and white company bosses, and strengthen collaboration between white and black coworkers instead. That was the key to what the black and Latino workers managed to pull off in Chicago.

Said Maclin in a 2009 interview:

I really think that what the workers at Republic Windows and Doors did was a model for the nation. Just think about it. We led; the politicians followed.”

Top Photo | Henry Nicholas, president of the National Union of Hospital and Health Care Employees, attends a protest by Philadelphia Council AFL-CIO on Wednesday, June 27, 2018, in Philadelphia. The protesters denounced Wednesday’s U.S. Supreme Court ruling that government workers can’t be forced to contribute to labor unions that represent them in collective bargaining, dealing a serious financial blow to organized labor. Jacqueline Larma | AP

Jon Jeter is a published book author and two-time Pulitzer Prize finalist with more than 20 years of journalistic experience. He is a former Washington Post bureau chief and award-winning foreign correspondent on two continents, as well as a former radio and television producer for Chicago Public Media’s “This American Life.”

The post The Upside of Janus: Court’s Ruling on Dues Check-Offs Could Help Democratize Unions appeared first on MintPress News.