Philadelphia

In May, Trump issued an executive order calling for Interior Secretary Doug Burgum to “ensure” that content which “inappropriately disparages” U.S. individuals past or living ceases to exist at national parks, including Independence National Historical Park in Philadelphia. In 2026, this INHP will be at the center of the celebration of the country’s 250th anniversary.

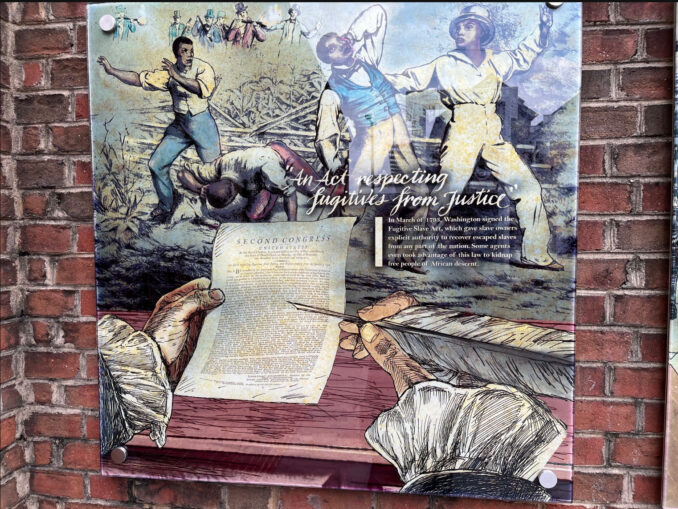

Panel depicts Washington’s signing of the infamous 1793 Fugitive Slave Act. Posse of white men with clubs and guns in the background shooting at four Black men escaping from enslavement. (WW Photo:Betsey Piette)

In just six weeks, over a dozen exhibits about enslavement at INHP could be removed or covered up, including materials at the President’s House Site, the Benjamin Franklin Museum, the Second Bank of the U.S., Independence Hall and an outdoor exhibit panel on Independence Mall.

But Trump’s campaign to ban any accurate depictions of U.S. history, in particular its racist roots in the enslavement of Africans, is running up against organized activists in Philadelphia determined to fight back.

Avenging The Ancestors Coalition (ATAC), which led the historic fight from 2002 to 2010 to include recognition of enslaved Africans in the INHP displays, held a press conference attended by over 100 people at the President’s House Site on Aug. 2 to announce their campaign to fight Trump’s censorship.

Fight to include enslaved Africans’ history

In 2002, the Liberty Bell was moved to the northwest side of Independence Park at Sixth and Market streets, where the first “White House” — occupied by U.S. Presidents George Washington from 1790 to 1797 and John Adams from 1797 to 1800 — was located. Built by Robert Morris, a financier of the Revolutionary War who made his fortune from the slave trade, the house was torn down and its foundation covered in 1832.

Panel at the President’s House Site bears names of nine African workers enslaved by George Washington. (WW Photo: Betsey Piette)

While historians were aware that Washington enslaved 316 people at his Mount Vernon plantation in Virginia, lesser known was that Washington brought nine enslaved Africans to Philadelphia, where slavery was illegal. The new location also held burial grounds with remains of the Africans enslaved by Washington.

When the National Parks Service (NPS) made the decision to relocate the Liberty Bell, they chose to ignore the full history of the site, including the areas where the nine enslaved individuals were quartered behind Washington’s house. In response, ATAC, under the leadership of progressive Black attorney Michael Coard, organized, fought, protested, held meetings and demonstrated to compel the INHP to agree to the creation of a prominent Slavery Memorial to highlight the President’s House project.

Funded by Philadelphia and federal money, the President’s House Site was opened in 2010 and later transferred to NPS ownership in 2015. During construction of the site, archeologists involved in the excavation explained the site’s history to a steady stream of people passing by, pointing out where the nine Africans worked and lived and how their activities were hidden from anyone walking by the house on Market Street. The building’s foundation is still viewable, encased in glass.

Say their names

The site tells the stories of the nine enslaved people: Austin and Paris — horsemen and stable hands; Hercules — the chief cook; Christopher Sheels — Washington’s personal attendant; Richmond — Hercules’ son and kitchen worker; Giles — a driver and stable hand; Ona Marie Judge — Martha Washington’s personal maid; Moll — nursemaid to the Washington’s grandchildren; and Joe Richardson — a stable hand.

The site highlights Washington’s signing of the infamous 1793 Fugitive Slave Act that put those who escaped enslavement at risk of recapture for the rest of their lives. Artwork on this display shows Washington’s hands holding a quill signing the Act, with a posse of white men with clubs and guns in the background shooting at four Black men escaping from enslavement. After this act was signed, Ona Judge successfully escaped enslavement by the Washingtons in 1796.

The exhibit, on Trump’s targeted list, focuses on the contradictory coexistence of liberty (for whites) and enslavement for Africans. One panel called “Life Under Slavery” illustrates the whippings, deprivation of food, clothing and shelter, beatings, torture and rapes endured by enslaved people. Other displays on Trump’s list include “The Dirty Business of Slavery” and “The House and the People Who Worked & Lived in It.”

At the press conference, Michael Coard told the crowd: “You can talk about George Washington being a great president, if you want, but can you be a great human being when you held 316 fellow human beings in brutal bondage under slavery? The content about Washington that was flagged for Trump’s review is historical fact.” Coard called for building a bigger, better, broad-based, multiracial coalition to take on Trump’s threats.

Roz McPherson, the original project manager for the President’s House Site who organized and chaired the press conference, called the rally “a starting point for a strategic effort to protect this important aspect of U.S. history.” McPherson repeatedly shared the text number 856-249-7874 for people in Philadelphia and outside to send their contact information if they want to be involved.

Liani Roundtree Johnson, an educator, said that while schooling may have left out the violence of slavery, places like the President’s House Site help fill gaps in people’s understanding of history. “How can we expect our young children to be change-makers and revolutionaries if we don’t educate them? We cannot.”